Devlog #2: Automating the convoluted stuff

Update 18 Jan, 2025: I figured out that all I needed to do in order to get around the impetus of this whole script was to add blank=True to each of my model's x_neighbor keys. Let this be a lesson that people much smarter than I have almost certainly solved any problems that I want to make for myself. But hey, it was a good lesson and the script itself has still proven useful several times over within the last few days.

As a self-proclaimed terrible Pythonista, I try to use the language to automate its own housekeeping whenever I can. This is starting to feel especially necessary as I continue to implement Django on top of what little Python I understand. Thankfully, Python has, like it so often does, a module for that.

For some context, I use Django's built-in TestCase module whenever I am able. One of the nicest things about using Django unit testing as such is that I can set up a specific group of Django models off of which I can then base my tests. Django runs the setup, runs the tests, and then wipes out the test DB so that I can start fresh next time. Nice! But sometimes, I just really like to have some "working storage" available to me. A sort of pre-built, reality-adjacent environment more akin to a snapshot than a sterile test environment1. So a less sterile test database that maintains changes has been a boon over the last few months of work.

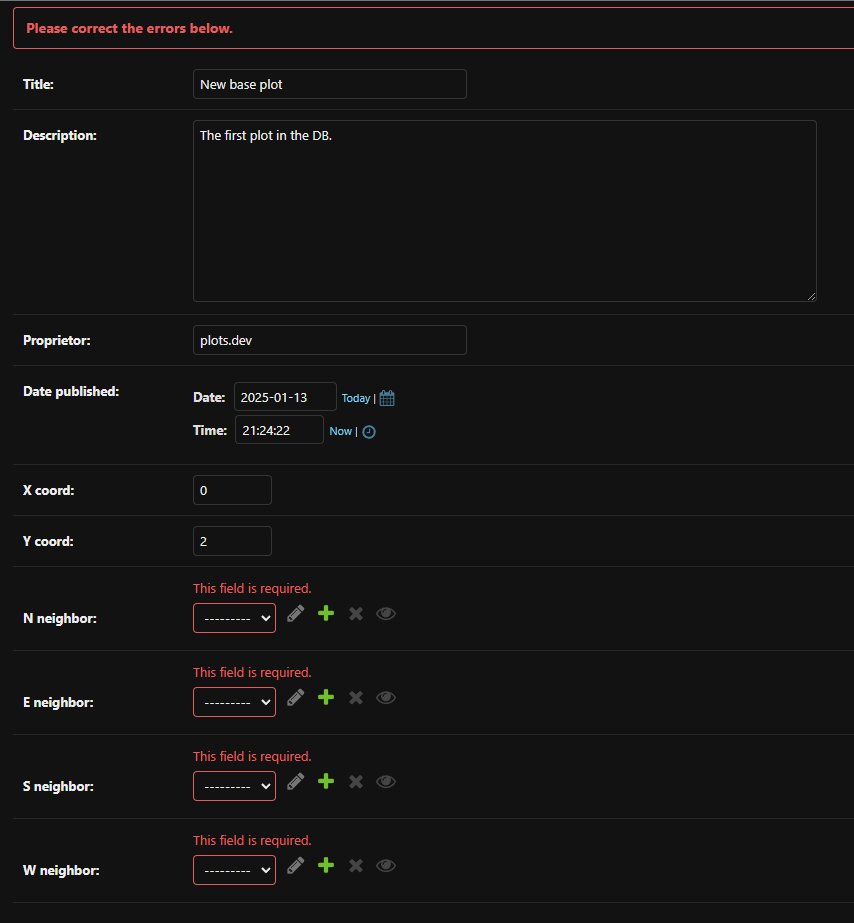

On paper, this isn't such a big deal, apart from the fact that the first plot I create within a given plot is unique. When a user creates a new plot, they need to be hooked up to a pre-existing neighbor. Except... if I'm creating the first-ever plot in a given database, it won't have any neighbors, and therefore my neighbor-hooking logic is dead on arrival. Have no fear - manually plugging that single plot in as a unique instance of a Django DB Model instance is not too big of a deal. Except... Django's admin panel expects that I hook it up to a pre-existing Plot model. It's a strange little quirk that I've found with the Admin panel. Certain model fields are allowed to be null, but if you're manually entering fields with a OneToOneFieldin the admin panel, it expects you to fill in all of these spots.

Which is a problem because, as discussed already, this is the first plot I'm adding back to the DB. The only way that I've found to get around this is to programmatically create this "parent plot" as if I was registering it via plots.club directly. Not a huge deal; I can just tweak a few parameters behind the scenes so that the next plot that's created on the site automatically sets all of its neighbors to null, save it off, and once I've confirmed that everything looks good, rip that hardcoded change out of the plot registration block.

A bit of a headache, but hey, I only had to do it once, right?

Except...

The bloat is real when you keep adding dummy plots and throwing spaghetti at the wall. Even using my unit tests as much as possible, I kept having to rebuild and re-seed my test database. And if I want to do this right, I really ought to be deleting the database outright every time, which also means that I wipe out myself as a superuser. So, in summary, I found myself in this coding loop:

- Find myself needing to do some manual, "closer-to-reality" testing that wasn't covered in my unit tests

- Build out real plots in my pilot database

- Repeat steps 1-2 for a couple hours' worth of work

- Realize that it's getting hard to navigate the plot space at this point, especially with the random errors / hookup issues that I've introduced to the DB because I was coding haphazardly

- Wipe out the database

- Dig up my randomly-saved-off couple of lines in a hastily-scrawled README (which serves as a collection point of reminders for the time being) and shove them into my plot registration path

- Spin up my server

- Register the new unique parent plot with all neighbors = null

- Rebuild myself as a superuser

- Check the admin panel to make sure that everything's looking good

- Return to step 1

Now, steps 4-11 are really only 10-15 minutes of work at worst, all told (7-8 minutes of which are me remembering where in the world I copied those injected lines off to), but it was annoying. And boring. And a repeated thing. And as we all know, devs are lazy and hate repeating themselves. So, what better way to save time than to automate this repetitive 10-minute process which I see myself continuing to do through the lifetime of this app?

First, all the snappy programs in the world don't mean much if you can't run them on the fly while working. Thankfully, there's an open-source collection of custom Django extensions available, aptly titled django extensions (link to the documentation). Pretty foolproof too, insofar as extensions go -- install using your REPL shell (via pip, etc.), add "django_extensions" to the "INSTALLED_APPS" section of your app's settings.py, and you're off to the races. Any Python file in your project that has a run() function defined in it can be run via your terminal. For instance, if you had such a function defined in a file named my_script.py, you'd run it by entering the command python manage.py runscript my_script. It's not even terribly slick, and yet... that's pretty dang slick.

Next, a realization that if I'm going to build a separate process to handle the re-seeding of a fresh DB, then I really ought to use said script to handle the entire DB re-seed / plot re-create / user re-build process, not just the two hard-coded lines of "base plot" creation. Enter the subprocess module (link goes to Python's official documentation). subprocess allows us to programmatically run terminal commands via Python code. Its run() method (seeing a lot of those today) is incredibly straightforward if you're on a Linux machine2 - simply provide a list of comma-delineated arguments as if you were typing said arguments in a terminal, and the module will run the arguments from the same level that the script was originally called at. The only "catch" here is ensuring the proper execution directory when firing all of this off. Not a huge deal -- in my case, it was straightforward enough for me to build a "scripts" folder at the parent level of my app (where manage.py lives) and call runscript from there, since that's where my terminal sits most of the time anyway (e.g. for spinning up my dev server, creating new django apps, and so forth).

The rest of the process ended up being as difficult as I wanted it to be. That is to say, I could have built a svelte six-line method to handle everything above. But for the sake of thoroughness (and not accidentally borking my own progress), I added a decent amount of handling and creature comforts; namely, I added a confirmation input, a try/except block, progress messages for visibility, and a few sleep() spots to make the process a little more human-readable.

Let's revisit those testing steps from up above with my new process:

- Find myself needing to do some manual, "closer-to-reality" testing that wasn't covered in my unit tests

- Build out real plots in my test database

- Repeat steps 1-2 for a couple hours' worth of work

- Realize that it's getting hard to navigate the plot space at this point, especially with the random errors / hookup issues that I've introduced to the DB because I was coding haphazardly

5. Wipe out the database - Dig up my randomly-saved-off couple of lines in a hastily-scrawled README (which serves as a collection point of reminders for the time being) and shove them into my plot registration path

- Spin up my server

- Register the new unique parent plot with all neighbors = null

- Rebuild myself as a superuser

- Check the admin panel to make sure that everything's looking good

- Return to step 1 (5.) Run py manage.py runscript (new method)

- (6.) Return to step 1

For what it's worth, outside of some documentation-perusing, this whole process was nigh-frictionless. It's taken me ~3x longer to write this devlog post about the process than it took me to figure this out. That said, I'm glad I've written it, if only to check my understanding as I go and in the hopes that I might help introduce these concepts to others along the way.

___________________________________

Upcoming topics I hope to tackle in future devlogs:

- Utilizing htmx in a django app

- Users and user authentication

___________________________________

1I'm aware that there are literally "snapshot tests," yes. I suppose that this is likely 50% me having (or thinking that I have) a unique enough situation with these plots that it'd be tough to emulate a repeatable test scenario, given that part of the app has randomness baked into it, and 50% me just not knowing enough about test frameworks. Something to look forward to as I build out my knowledge!

2the process is less straightforward if you are not on a Linux machine, or running macOS. As a Windows user, I had to do a little more fiddling to get my commands to a good place. There is thankfully plenty of documentation out there that got me to a good place, but the long and short of it is that, if I wanted subprocess to behave as if it were the command line terminal, I had to begin each list of arguments with 'cmd', then '/c', and then proceed with my actual command, as well as figure out all of the Windows-specific commands that I'd need to use in place of the Linux terminology which is more ubiquitous in these types of documentation. In short, something like subprocess.run(['ls']) becomes something like subprocess.run(['cmd', '/c', 'dir']). Not quite as spiffy, but I'm not complaining.